MSW Alumna Virginia Castro

Chicano civil rights activist Virginia Castro was ‘destined’ for a career in school social work

Education and activism have shaped Virginia Castro’s life.

In the 1960s, the Chicano civil rights movement — El Movimiento — was taking root in cities across the U.S., including Denver. Castro was introduced to the movement as a student at Metro State. “The Chicano students were organized at that time,” recalls Virginia, MSW ’73. “They seized the reins in my life.”

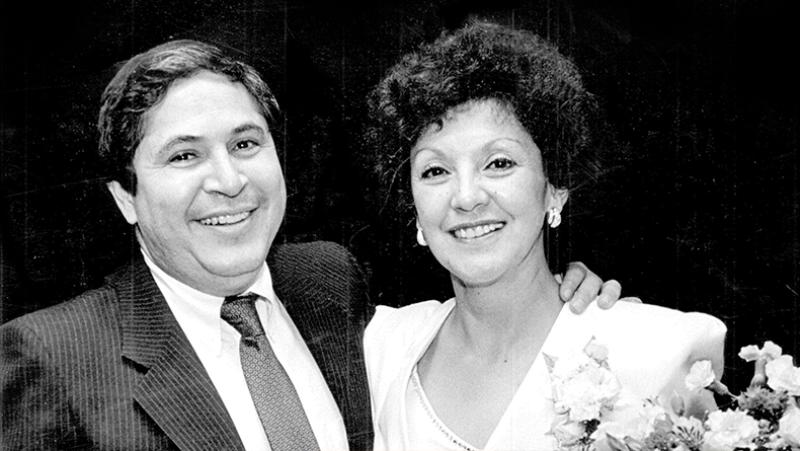

The movement is how she met her second husband, the late Richard Castro, MSW ‘72, who went on to become a five-term Colorado state representative, a member of Denver’s board of education, and director of Denver’s Agency for Human Rights and Community Relations. When they met in 1967 as college students, Richard was a year ahead of Virginia and was “meeting new students, talking to them, educating them about why it was important to be part of this group. That’s what I did for the rest of the five years that I was there.”

Virginia followed Richard to the University of Denver Graduate School of Social Work (GSSW), and in 1974, Virginia began her nearly three-decade career as a Denver Public Schools (DPS) social worker. At West High School, she created the city’s first program for teen moms, contracting with a nearby daycare center to watch children while their mothers attended class and with a cab company to drive them. As manager of DPS Social Work Services from 1991 to 2001, Virginia founded a successful citywide truancy-reduction program.

An American success story

Virginia Castro’s biography reads like a classic American success story. She was born in Silt, Colorado, where her grandparents owned “a little patch of land” they’d bought with her granddad’s railroad wages. They’d arrived from Mexico in 1925 as migrant workers recruited to labor in Western Colorado’s cantaloupe fields and peach orchards. When Virginia’s grandfather died, his 14-year-old son, the eldest of seven children, took a job on the railroad to support the family.

Virginia’s mother was born in Mexico and was a young girl when her parents immigrated to the U.S.; her father was a migrant worker from New Mexico. Halfway into her senior year in high school, Virginia dropped out of school to take care of her dying grandmother.

Virginia had met her first husband in high school. Four children later, the marriage ended and Castro found herself a single mom trying to make it in Denver.

“It was just meant to be that I was not going to be a stay-at-home mom,” Virginia says. “My aunt had gone to nursing school, and I always admired her.” Virginia enrolled in opportunity school, earned her GED and completed nursing training. The next year, 1967, she enrolled in Metro State intending to pursue nursing, and “my world opened up.”

She was empowered by the work she and other Chicano activists were doing to help students get into college and succeed once they were there. “Many of the students were just recently returned from Vietnam and were having some real problems,” Virginia recalls. “That’s how the social work world opened up to me. I was destined to go into social work.”

Her path wasn’t easy. “My two youngest children went to Head Start, so during the day, the kids were all in school. Thank God for Head Start,” Virginia says. “For the nursing program, I had to be at Denver General at 7 a.m., and I had no transportation. I had to take the bus, and I lived about a mile from the bus stop. I had to depend on a neighbor to get my little ones to Head Start, and the other two walked to school.

“I had to depend a lot on my oldest son, who was in elementary school,” Virginia recalls. “I trusted him to put potpies in the oven and feed the kids when I couldn’t be there for dinner.” Virginia studied at night after the kids had gone to bed.

Activism was a family affair, Virginia says. “As far as the movement was concerned, we did a lot of protesting, boycotting. I took the children with me.”

Social work in the civil rights era

“I had a wonderful [GSSW] professor, Jules Mondschein. He had so much faith in me,” Virginia recalls. “He was mesmerized by Rich and my involvement in the movement. He let us do an individual program in community organization.”

Virginia and Richard worked to recruit Chicano professors to DU and encouraged the school to assume an expanded role in the community. “We got a professor placed at the Auraria Community Center at 12th and Mariposa, and we had around 12 DU graduate students at the center, where they did their field placement,” says Virginia, who worked at the center after graduation.

It was then, she says, that she discovered a passion for working with youth. “Rich was off on his political career. He ran for state representative,” she says, “and in 1974 I started my job with DPS and he went to the House of Representatives.”

Virginia had wanted to work with high school students where there was a large Chicano population. Instead, she was assigned to be a social worker at Grant Middle School in Denver’s Washington Park neighborhood. There was one black teaching assistant, and Virginia was the only Chicano in the school; all the teachers were white. “I started my career working with only white students. I really had to open up my vision of social work to include everybody.”

Following a 1974 Supreme Court ruling to desegregate Denver schools, the city started mandatory bussing, and black and Chicano middle school students from Curtis Park and Five Points were bussed to Grant. “That was an amazing, troubled time,” Virginia recalls. “Out in the community, people were having a real problem with this bussing situation. The kids picked up on the fact that they weren’t supposed to get along. We had fights on the busses; we had kids hurt sometimes.”

The simmering racial tension created an atmosphere where teachers couldn’t teach, Virginia recalls. So, the Grant teachers broke kids up in groups. “I took the Chicano students, the assistant took the black students, and we had heart-to-hearts with the kids.

“We had to start from scratch teaching them to just be kids and be in school,” she continues. “One of the teachers started some teams — a basketball team, volleyball — and little by little the kids just started being kids.”

Virginia stayed at Grant for six years and spent the next five at West High School. “I loved that school. It was just exactly where I felt I could do the best work,” Virginia says. “I think we had 1,700 kids there, and I had a case load of 600.”

At West, she kept “losing kids.” “I asked for a list of the dropouts. The secretary pointed at two metal boxes. One was the students who were there, the other was the students who were gone, and they were both about the same size.

“I thought, ‘This cannot be possible that this school cannot know the kids who are leaving and do anything about it,’” Virginia recalls.

Resolved to do something about it herself, Virginia contacted students, studied policies, and learned that many of the dropouts were young women who’d become pregnant. She responded by starting the district’s first program for teen mothers. Eventually, the program merged with another and today lives on as the Florence Crittenton High School for pregnant and parenting teens.

For Virginia, education, social justice, and social work are intertwined.

“From the point of view of someone who spent 27 years in the schools, the most important thing is for kids to stay in school,” Virginia says. “It doesn’t have to be such a negative experience for them. There are schools that are very successful. They have happy kids, they love their experience, they achieve. Why is it that we have so many schools that don’t?

“School is a place where we can teach our kids how to get along, how important they are,” she continues. “We have to help kids develop themselves as caring human beings who understand the different problems and situations that everybody else shares.”

A lasting legacy

Virginia served on Denver’s Commission on Mental Health and Department of Human Services Advisory Board, received a DPS Service Award and was honored by the National Association of Social Workers as a School Social Worker of Distinction.

After Richard’s sudden death in 1991, Virginia established the Richard T. Castro Memorial Scholarship fund at GSSW. Virginia and Richard received a 2017 GSSW Dean’s Award.

Virginia retired in 2001 but remains involved at Denver’s Richard T. Castro Elementary School. (The Denver Department of Human Services building also is named for her late husband.)

Helping kids is still a passion. “My experience is that if you are honest with youth — truly interested in who they are, what they have to say, what they have to contribute — you can do wonders.”

Read more about Richard T. Castro in The Life and Times of Richard Castro: Bridging a Cultural Divide by Richard Gould.