A Poetic Witnessing

Beltrán first met Yazzie several years ago through mutual friends; the artist and the scholar–artist quickly found common ground. Yazzie offered to help Beltrán with the Our Stories, Our Medicine Archive (OSOMA) of Indigenous health knowledge, and Fermin joined the OSOMA team as well. Yazzie later joined the University of Denver’s IRISE research institute as a visiting scholar. With the OSOMA project, Beltrán says, “he was able to translate my ideas into something better and more beautiful.”

Beltrán had introduced Yazzie to the qualitative research method of poetic analysis, an arts-based research method that translates data into creative representations. He subsequently invited her to apply the method to the focus group data. To develop the poetic script used in the film — what she describes as a “poetic witnessing” — Beltrán listened to the audio recordings of focus group sessions several times, noting the most repeated and salient topics. She then created poems from participant quotes.

“The poems ended up being the blueprint for the documentary,” Beltrán explains. The film comprises four parts, each including a segment of Beltrán’s poem juxtaposed with fictionalized vignettes in which community members act out intimate, nuanced conversations about some of the thorny social issues that emerged throughout the data. “The poems were the beautiful part — the things people said that were complex but still loving and kind and connected.”

Beltrán acknowledges that although much of the film celebrates beauty, other parts can be deeply uncomfortable to watch. In Beltrán’s favorite scene, two friends — one Native, one white — have vastly different responses to Cree artist Kent Monkman’s painting “The Scream,” which depicts the horrors of child removal and the Canadian Indian residential school system. “It’s violence,” the Native observer says to his friend, who sees something very different. The conversation devolves into a physical fight — a metaphor for the racialized tensions and interpersonal and systemic violence Denver’s residents experience.

As a trauma-informed social work scholar, Beltrán says she was concerned about the potential for the experience of watching “Knowing You, Denver” to be harmful for viewers. She says, “As an art piece, I found this to be really challenging. I had to work through my own feelings about the content. But art is necessarily evocative and invites people into thinking about things critically in a more embodied way.”

The Native protagonist in the film’s final vignette acknowledges and responds to the viewer’s discomfort: “That’s why you come to museums: to challenge yourself.”

Ultimately, Beltrán says, community feedback shaped all aspects of the film, from the locations to the script to the voiceovers and the film’s overall look and feel. “This method and the outcome is a shared art experience” that includes the viewer as well.

Beltrán continues, “Art is so powerful — it speaks the language of the heart. It’s about nuance and about getting deeper into the essence and experience of things. Art in research does that, too.” She adds, “Where I found some relief from my worry was understanding that these topics came from the data. Part of the challenge now in this political moment is having difficult conversations around complex, sometimes polarizing social issues. Art can open up dialogue around these things.”

“Knowing You, Denver” isn’t Beltrán’s first foray into what she calls “scholARTship.” In addition to her ongoing work with OSOMA, she produced “The Source of the Wound,” an award-winning animated short film exploring historical trauma and healing in Native and Indigenous communities. She says, “I really want to lean into my authentic voice and use the methods and tools that speak most directly to my community in the language we all understand.”

Beltrán would like to see more social work scholars applying creative methodologies. “When we’re so focused on our discipline and methods, we can miss a bigger picture of the world. That is a limitation — we should exchange ideas to really get somewhere in terms of language and meaning that translates into policy and action. That’s where I see possibility … to bring data to art and art to data.” Art, Beltrán adds, recognizes that the audience also has a contribution to make in the way they interact with and perceive the art. She says that shared experience is “beautiful and a way to disrupt the colonial hierarchy we’ve inherited about what counts as knowledge.”

As an editorial board member for the feminist social work journal Affilia, Beltrán will be revitalizing the journal’s poetry component and expanding to include other types of creative work as well, redefining ideas of what belongs in a peer-reviewed journal. In a forthcoming editorial in the journal, Beltrán writes about her recent experience attending the first Federal Indian Boarding School Healing Summit, where Lakota artist and boarding school survivor Dora Brought Plenty said, “Art saved my life. It continues to save my life.”

That powerful healing potential is something social work and the greater world needs more of, Beltrán says. “Knowledge and meaning making and creativity are our inheritance. It’s a gift we have received from our ancestors, and it’s a gift we give back to those ancestors and the generations to come. We leave a record of our lives, and they get to build from that.”

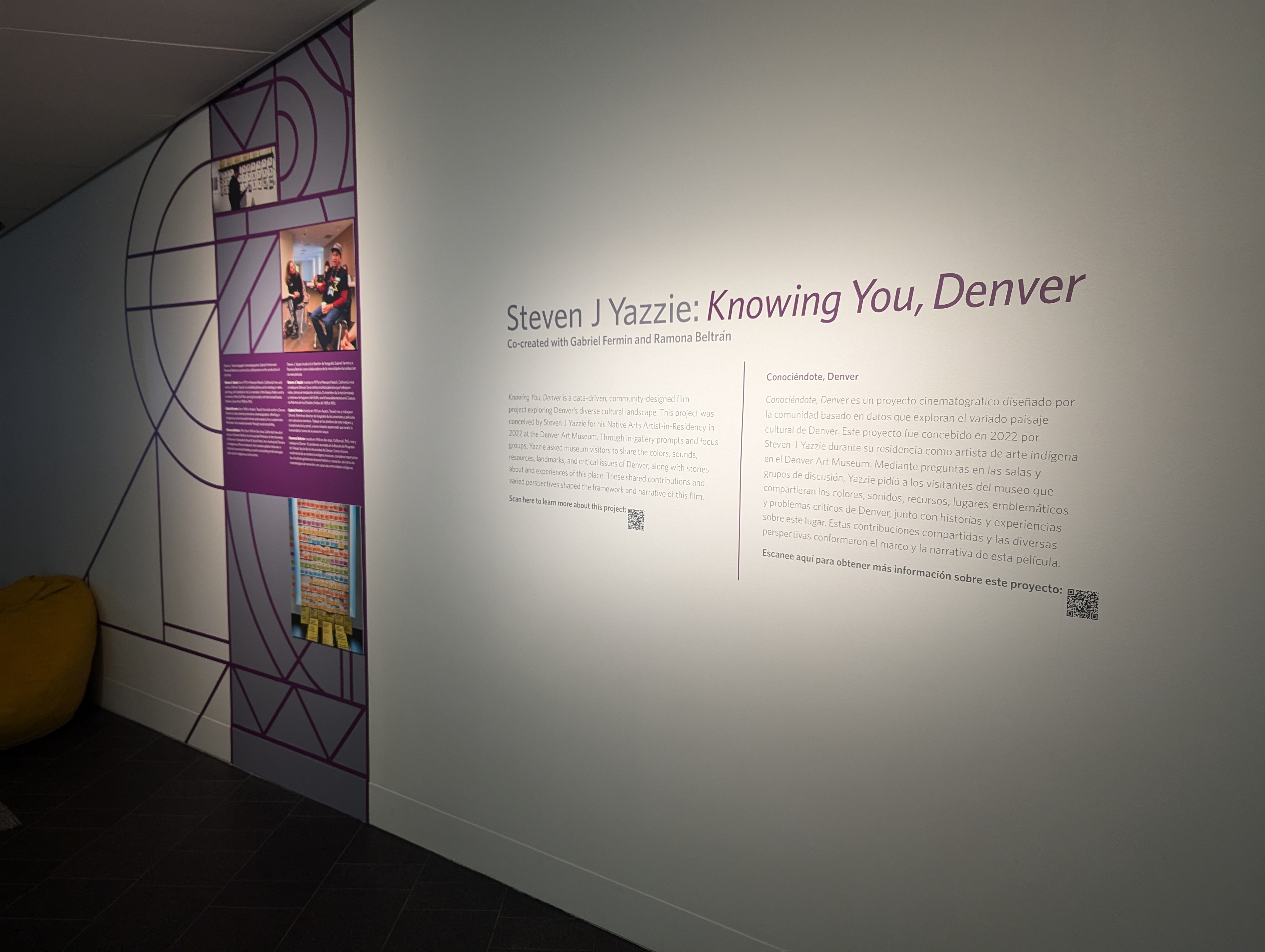

“Knowing You, Denver” opened in August 2024 and is currently on display on level 3 of the Denver Art Museum Hamilton Building (a closing date for the installation has not yet been announced).