University of Denver Graduate School of Social Work (GSSW) Assistant Professor Sophia Sarantakos says they’ve been thinking like a futurist their whole life. As a person who has identified as queer since childhood, Sarantakos says, “The present was never safe or comfortable, so envisioning an eventual reality that held me with care was a practice of hope and survival.”

As an abolitionist, Sarantakos is working toward a liberatory future. They now are learning to apply formal futures-thinking tools to their work as a Health Futures Fellow of the Portland State University Social Work Health Futures Lab, a program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Learn more about the Social Work Health Futures Lab.

Read More

“If we’re talking about a healthy future for everyone, that future must be free from state abandonment and violence,” says Sarantakos, one of 26 social work fellows from across the United States and Canada who represent a broad array of research interests and backgrounds. Over 18 months, the fellows will learn to apply a futures lens to urgent social problems, including racial justice.

An emerging transdisciplinary social science, futures thinking — or foresight — is a practice of thinking about the future in a structured way. It looks around corners to identify and understand all possible futures and their respective risks and opportunities.

“This initiative provides a new kind of space for social work to imagine our role in the world that is unfolding right now, and in the years to come especially as it relates to the health and well-being of communities and to the future of health and human rights,” says GSSW alumna Laura Nissen, founder and director of the Health Futures Lab and an advocate for including futures and foresight methods in social work practice.

GSSW alumnus Finn Bell, MSW ’09, is a Health Futures Fellow and a doctoral student at the University of Michigan School of Social Work. With an interest in how communities can build the emotional, spiritual and cultural sustenance needed to address the climate crisis, his dissertation research explores the ways that growing food is an act of resistance and builds resilience for Black, Indigenous and people of color and working class communities.

“The Health Futures Fellowship is organized around the social determinants of health, and climate change impacts every determinant and will amplify injustices,” Bell says. “No matter what issue you’re looking at as social workers, you have to take climate change into account — all of the vulnerable people we work with are hit first and worst. I wanted to be part of the conversations about the future of the field and how these trends are impacting social work.”

The Future of Social Work

The future of social work and social welfare is a central conversation at the Health Futures Lab.

Nissen (GSSW MSW ’89, PhD ’97) is a professor of social work and Presidential Futures Fellow at Portland State University and a research fellow at the Institute for the Future, the world’s leading foresight education and futures organization. She became interested in futures thinking while working on her doctoral dissertation exploring innovations in macro-level systems change. After graduation, she went to work for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, where she led the Reclaiming Futures juvenile justice reform initiative. There, she hired a futurist to be part of her team.

Reclaiming Futures was supposed to be a five-year project but is still going strong more than two decades later. “We planned with a futurist, and almost everything we anticipated came to pass,” Nissen says. Applying a futures framework to long-term planning “made us more agile, creative, collectively intelligent.”

Nissen reengaged in futures work several years ago and noticed that social work was largely absent from futures conversations. “I went to all these futures meetings that were intensely interdisciplinary — talking about things like the future of work, artificial intelligence — and there were no social workers. And I’d go back to my social work meetings and we weren’t talking about these things at all,” Nissen recalls. “Social workers need to be in these conversations but also cultivating our own contributions.”

Learn more about Laura Nissen’s social work futures thinking on her website and blog.

Read More

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation agreed and tapped Nissen to run an experiment: What happens when you provide futures-thinking training to social workers?

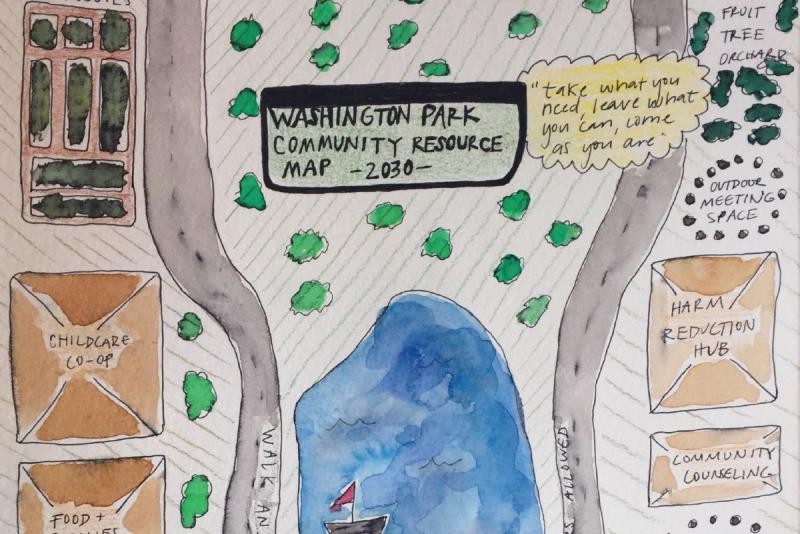

GSSW PhD student and Health Futures Fellow Danielle Littman is broadly interested in expanding the ways we think about social work, health and well-being. With a research interest in mutual aid and collective care and a background in the arts and the integration of the arts and social justice, she says, “I was craving the space where we could take a step back and look at things from different angles.” The fellowship provides that space for creative thinking, imagination and risk taking.

“If we keep doing the exact thing we’re doing now in social work in 20 years, 30 years — what’s going to happen to the world?” Nissen asks. “And what’s going to happen to the profession of social work if we’re not in these conversations? We risk being left behind. You start where people are and invoke their own imaginations. Learn some new tools, get out of social-work centric spaces, be willing to get uncomfortable.”

Some of those uncomfortable conversations center on decolonizing social work and decentering white supremacy in planning for the future. Although there has been a rich tradition of futures thinking in marginalized communities, formal futures frameworks have largely been tools of the rich and powerful, says Nissen, who hopes to help democratize and amplify their use through social work.

“Futures frameworks are powerful frameworks to imagine equity,” says Nissen. “Futures work is about reminding us that we have this most incredible tool, our imagination, to solve problems with.”