The Future of Social Work

Author(s)

Dean Amanda Moore McBride reflects on what the next century might look like for social work and GSSW

Morris Endowed Dean and Professor Amanda Moore McBride embarked on her sixth year at the helm of the University of Denver Graduate School of Social Work (GSSW) this fall, which also marks the school’s 90th anniversary. Dean McBride reflects on what the next 90 years might look like for social work and GSSW and shares her vision for a more caring, connected future.

Q: GSSW is celebrating its 90th anniversary this year. What are some of the most significant shifts in social work practice and education over the past century, and how did the profession arrive at this moment?

A: My hope is that social work is becoming more self-conscious, more responsive to community, more aware of its harmful history, more just going forward. Over the past century, social work has spent a lot of time on its “professionalization” and justifying itself as a field. We need to be self-critical not only of that professionalization but also our racist and problematic foundations and approaches. Social movements of the last five years — such as Black Lives Matter and #MeToo — and concerns regarding climate change have awakened (or reawakened) a macro sensibility in social workers, highlighting the importance of policy, civic engagement, and mutual aid for systemic change. At the same time, we’re seeing social workers in industries and areas of practice that we weren’t in 20 years ago. We are bringing our person-in-environment framework, identification of systemic inequities within organizations and ways to change them, and knowledge of the vast resources that can be marshalled to help individuals succeed in work and life. Social workers are increasingly serving as facilitators, bringing a commitment to anti-racist practice to human resource departments, community schools, and diversity, equity, and inclusion programs.

Q: Futurists often attend to signals — signs in our everyday lives that, when put together, signal future trends. What signals have you noticed that you think we need to pay more attention to as social workers?

A: The first signal is contradictory: How can we de-professionalize when it could be argued that everybody needs a social worker? De-professionalizing demands that we recognize how social work has destabilized communities, especially communities of color, by stepping in to “provide care” when our “help” wasn’t needed. Yet, realizing our possible value asks us to define our proper role: How can social work maximize systems of collective care?

The second signal relates to the use of technology in social work. I think of it in two ways. One is the use of technology such as telehealth to increase access to services. What does it mean to make this standard practice, and how do we train students on the ethics of utilizing technology? The other area connected to technology — and I just love that GSSW has faculty who are experts in this — relates to artificial intelligence, the algorithmic nature of social media, the surveillance systems in our devices. What does it mean to apply a social- and racial-justice orientation within social media algorithms?

Another signal to watch is related to climate change. Social workers need to support grassroots organizing, the collective action necessary to push for policy change. Social workers play an important role alongside engineers, geologists, and policymakers—we bring the people perspective. We also need to respond to the growing mental angst that many people have around the climate crisis, especially our youngsters. What does it mean to be a support but also to follow this generation into action?

A final signal relates to capitalism. Our larger economic system has dictated our social system. So many of the issues that social work aims to address are because not all people can survive, let alone thrive. The pandemic has laid this fact bare. Imagine a social democratic state centered on humanism not capitalism; imagine an economic order held to a triple bottom line of planet, people, and profit; imagine talents unleashed that enable humans to realize their highest potential in and through community; and imagine a netted system of social and health supports that increase access to that potential for all. All of this is possible. Social workers can help to lead the way.

Q: Looking ahead to the next 90 years, where do you see social work headed? How do you anticipate the social work of the future differing from the social work we know today?

A: When GSSW engaged in strategic visioning almost five years ago, community members said what they need from social work is support for residents in how to be effective peer navigators — someone who has lived experience in an issue who also wants to know more about the issue and how best to engage with their neighbors on it. GSSW has training programs and conducts research in urban and rural areas, and we are guided by our partners in these locations. The community’s request is still predominant. How can social work better support paraprofessional social work and be a resource for collective care and community action? I am delighted that more and more GSSW faculty are studying peer-based interventions. When I look ahead to the next 90 years for GSSW and social work overall, we need to decenter the social worker and center the person.

Q: How does a school of social work like GSSW begin to make that shift to actively engage the future you just described?

A: I think the master’s degree as it is currently packaged will be a harder sell 10 years from now — let alone 90 years from now. The signals are already here. Online education is now standard across higher education, with training at our fingertips. One-year master’s and certificates are emerging at scale, be they in diversity, equity, and inclusion or “life coaching” or trauma-informed care. Training is also being offered by organizations outside of higher education.

At the graduate level, I think higher education must move to a more bite-sized type of education. GSSW is exploring possibilities in this area. For example, our Office of Community Engagement is offering certificate programs that are a shorter time commitment and give social workers the skills and credentials they need to make a shift in their career. Right now these are postgraduate opportunities, but what if they were pre-graduate and that training counted toward the master’s degree? I envision us building out more of these types of continuing education opportunities and offering them to folks across their careers.

At GSSW, we’re also exploring shifting our MSW concentrations to pathways with flexible requirements. Students could find their own ways across the curriculum based on their interests. There would be more flexibility in the courses that they take to meet requirements. We also continue to expand the curriculum, offering more courses in areas such as the criminal legal system and ecological justice, which allow students to learn more about substantive areas while they develop skills in individual, group, or community work. Our education and training must be anti-racist, accessible, and relevant—now.

Learn more about options for lifelong learning, including practitioner continuing education and our Civic Series

Learn More

Q: What are some of the biggest challenges you anticipate for the profession, now and in the coming years, and what should social work schools do to prepare?

A: To be relevant 90 years from now, in 2111, social work must be an anti-racist and much more diverse profession. If we do not address the white supremacist roots of both social work and higher education, social work will fail. We must change the practices and approaches that have eroded community and systems of care within Black and Brown communities and the training that perpetuates that erosion. Changing both MSW and doctoral education is a must.

Q: Multiple futures are possible, and some may be more radical or transformative than others. What radical, transformative future do you envision for social work?

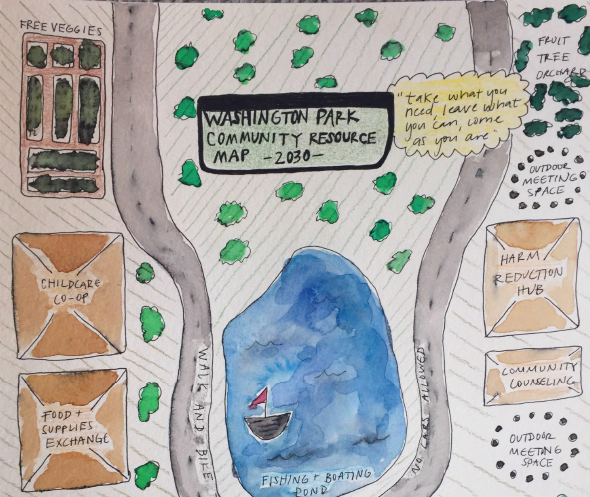

A: The medical model separated mind and body, and overall, social work adopted that conception. Social work should break down this false duality between mind and body and revolutionize what mental health practice looks like through embodied practice. I also envision social workers as civic and community coaches who support mutual aid and collective action efforts. What would it look like to train ourselves to train others? Let’s sow seeds now for the community organizing that will be needed in the 22nd century.

Q: Now is a particularly difficult time to be a social worker — perhaps one of the more difficult times in the history of the profession. What words of encouragement do you have for the future social workers GSSW is educating now?

A: Ninety years ago, the U.S. was about to enter a world war; there was great poverty and destitution. And yet, social workers helped put social policies into place that are still supporting people today. What is the New Deal for today and tomorrow and the next century? We need a new social contract, and we need it fast. We can envision a better future, and we have civic tools to make it a reality. This power gives me hope that social work can help create a more just and caring society.